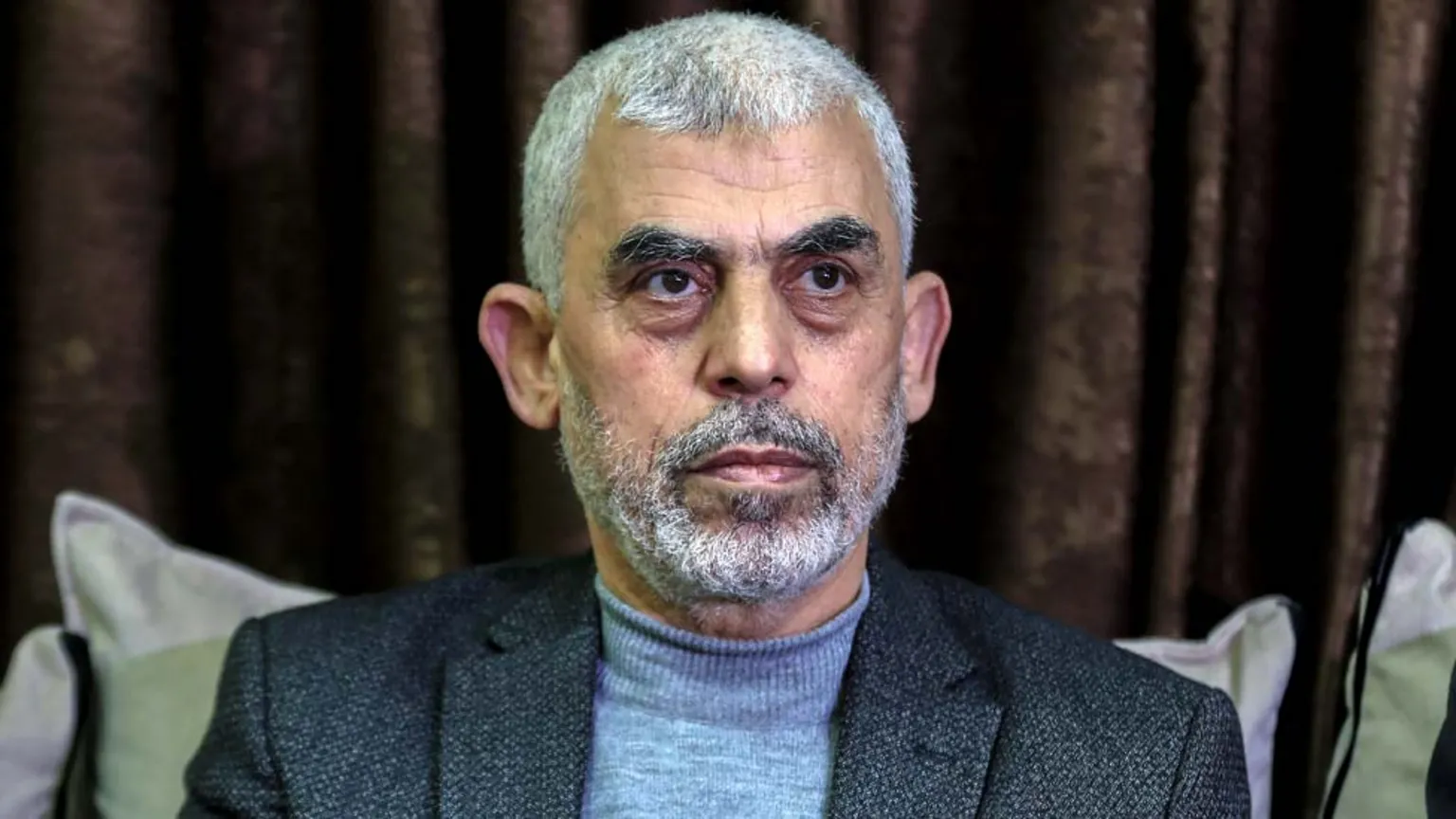

Israel says its troops in Gaza have killed Hamas leader Yahya Sinwar, a chief architect of the 7 October 2023 attacks and the country’s most wanted man.

Sinwar disappeared at the start of the war triggered by the unprecedented Hamas attacks, in which about 1,200 people were killed and 251 others were taken hostage.

That was hardly surprising, as thousands of Israeli troops backed by drones, electronic eavesdropping devices and human informants, tried to discover his whereabouts.

“Yahya Sinwar is the commander… and he is a dead man,” declared Israel Defense Forces (IDF) spokesman Rear Admiral Daniel Hagari at the time.

It was assumed that Sinwar spent much of the past year cornered below ground, hiding in tunnels somewhere beneath Gaza with his bodyguards, communicating with very few people for fear that his signal would be tracked and located. There were also fears that he would surround himself with Israeli hostages as human shields.

But in the end, soldiers operating in southern Gaza killed Sinwar inside a building where there was no sign of any hostages being present, according to the IDF. It announced his death on Thursday, after identifying his body using fingerprint and dental records.

“He who carried out the worst massacre in our people’s history since the Holocaust, the arch-terrorist who murdered thousands of Israelis and kidnapped hundreds of our citizens, was killed today by our heroic soldiers,” Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said. “And today, as we promised to do, we settled the score with him.”

Israel has already killed many other senior Hamas figures in Gaza, who were all declared “dead men walking” following the 7 October attacks.

They included Mohammed Deif, the leader of Hamas’s military wing, the Izzedine al-Qassam Brigades, who the IDF said was killed in an air strike in Gaza in July.

Hugh Lovatt, senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR), said last year that he believed Deif was the brains behind the planning of the 7 October attack because it was a military operation, but that Sinwar “would likely have been part of the group that planned and influenced it”.

Hamas also accused Israel of assassinating its overall leader, Ismail Haniyeh, in Tehran in July. Despite being on the run, Sinwar was named as his successor the following month.

Upbringing and arrests

Sinwar, 61, widely known as Abu Ibrahim, was born in the Khan Younis refugee camp at the southern end of the Gaza Strip. His parents were from Ashkelon but became refugees after what Palestinians call “al-Naqba” (the Catastrophe) – the mass displacement of Palestinians from their ancestral homes in Palestine in the war that followed Israel’s founding in 1948.

He was educated at Khan Younis Secondary School for Boys and then graduated with a bachelor’s degree in Arabic language from the Islamic University of Gaza.

At that time, Khan Younis was a “bastion” of support for the Muslim Brotherhood, said Ehud Yaari, a fellow of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, who interviewed Sinwar in prison four times.

The Islamist group “was a massive movement for young people going to the mosques in the poverty of the refugee camp”, Yaari said, and it would later take on a similar importance for Hamas.

Sinwar was first arrested by Israel in 1982, aged 19, for “Islamic activities” and then arrested again in 1985. It was around this time that he won the confidence of Hamas’s founder, Sheikh Ahmed Yassin.

The two became “very, very close”, said Kobi Michael, a senior researcher at the Institute for National Security Studies in Tel Aviv. This relationship with the organisation’s spiritual leader would later give Sinwar a “halo effect” within the movement, Michael added.

Two years after Hamas was founded in 1987, he set up the group’s feared internal security organisation, the al-Majd. He was still only 25.

Al-Majd became infamous for punishing those accused of so-called morality offences – Michael said he targeted shops that stocked “sex videos” – as well as hunting down and killing anyone suspected of collaborating with Israel.

Yaari said he was responsible for numerous “brutal killings” of people suspected of co-operation with Israel. “Some of them with his own hands and he was proud of that, talking about it to me and to others.”

According to Israeli officials, he later confessed to punishing a suspected informer by getting the man’s brother to bury him alive, finishing the job using a spoon instead of a spade.

Yaari said he was “the kind of man who can gather around him followers, fans – together with many who are simply afraid of him and don’t want to pick any fights with him”.

In 1988, Sinwar allegedly planned the abduction and killing of two Israeli soldiers. He was arrested the same year, convicted by Israel for the murder of 12 Palestinians and given four life sentences.

The prison years

Sinwar spent a large part of his adult life – over 22 years – in Israeli prisons, from 1988 to 2011. His time there, some of it in solitary confinement, appeared to have radicalised him even further.

“He managed to impose his authority ruthlessly, using force,” said Yaari. He positioned himself as a leader among the prisoners, negotiating on their behalf with prison authorities and enforcing discipline among the inmates.

An Israeli government assessment of Sinwar during his time in prison described his character as “cruel, authoritative, influential and with unusual abilities of endurance, cunning and manipulative, content with little… Keeps secrets even inside prison amongst other prisoners… Has the ability to carry crowds”.

Yaari’s assessment of Sinwar, built up over the times they met, was that he was a psychopath. “[But] to say about Sinwar, ‘Sinwar is a psychopath, full stop,’ would be a mistake” he said, “because then you will miss this strange, complex figure”.

He was, Yaari said, “extremely cunning, shrewd – a guy who knows to switch on and off a type of personal charm”.

When Sinwar would tell him Israel must be destroyed and insist there was no place for Jewish people in Palestine, “he would joke, ‘Maybe we’ll make an exception of you'”.

While incarcerated Sinwar had become fluent in Hebrew, reading Israeli newspapers. Yaari said Sinwar always preferred to speak Hebrew with him, even though Yaari was fluent in Arabic.

“He sought to improve his Hebrew,” Yaari said. “I think he wanted to benefit from somebody who spoke higher Hebrew than the prison wardens.”

Sinwar was released in 2011 as part of a deal that saw 1,027 Palestinian and Israeli Arab prisoners released from jail in exchange for a single Israeli hostage, the IDF soldier Gilad Shalit.

Shalit had been held captive for five years after being kidnapped by – amongst others – Sinwar’s brother, who is a senior Hamas military commander. Sinwar later called for more kidnappings of Israeli soldiers.

By now, Israel had ended its occupation of the Gaza Strip and Hamas was in charge, having won an election and then eliminated its rivals, Yasser Arafat’s Fatah party, by throwing many of its members off the tops of tall buildings.

Brutal discipline

When Sinwar returned to Gaza, he was immediately accepted as a leader, Michael said. Much of this was to do with his prestige as a founding member of Hamas who had sacrificed so many years of his life in Israeli prisons.

But also, “people just feared him – this is a person that murdered people with his hands”, Michael said. “He was very brutal, aggressive and charismatic at the very same time.”

Yaari said he was “not an orator” and that when he spoke to the public it was “like somebody from the Mob”.

Yaari added that immediately after leaving prison, Sinwar also forged an alliance with the Izzedine al-Qassam Brigades and chief of staff Marwan Issa.

In 2013, he was elected a member of Hamas’s Political Bureau in the Gaza Strip, before becoming its head in 2017.

Sinwar’s younger brother Mohammed also went on to play an active role in Hamas. He claimed to have survived several Israeli assassination attempts before being pronounced dead by Hamas in 2014. Media reports have since surfaced asserting he may still be alive, active in Hamas’s military wing hiding in tunnels beneath Gaza and may even have played a part in the 7 October attack.

Sinwar’s reputation for ruthlessness and violence earned him the nickname of The Butcher of Khan Younis.

Yaari said he imposed “brutal discipline”, and that Hamas members knew that if they disobeyed him “you put your life on the line”.

He was reputed to have been responsible for the 2015 detention, torture and murder of a Hamas commander named Mahmoud Ishtiwi who was accused of embezzlement and homosexuality.

In 2018, in a briefing to the international media, he signalled his support for thousands of Palestinians to break through the border fence separating the Gaza Strip from Israel as part of protests over the US moving its embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem.

Later that year he claimed to have survived an assassination attempt by Palestinians loyal to the rival Palestinian Authority (PA) in the West Bank.

Yet he also showed periods of pragmatism, supporting temporary ceasefires with Israel, prisoner exchanges, and a reconciliation with the Palestinian Authority. He was even criticised by some opponents as too moderate, Michael said.

Closeness to Iran

Many in Israel’s defence and security establishment believe it was a fatal mistake to have let Sinwar out of prison as part of the prisoner exchange.

Israelis feel they were lulled into a false sense of security in the mistaken belief that by offering Hamas economic incentives and more work permits, the movement would have lost its appetite for war. This, of course, turned out to be a disastrous miscalculation.

Yaari said Sinwar saw himself as “the guy destined to liberate Palestine” and that he was “not about improving the economic situation, social services for Gaza”.

In 2015, the US State Department officially categorised Sinwar as a “Specially Designated Global Terrorist”. In May 2021 Israeli air strikes targeted his home and office in the Gaza Strip. In April 2022, in a televised address, he encouraged people to attack Israel by any available means.

Analysts identified him as a key figure linking Hamas’s political bureau with its armed wing, the Izzedine al-Qassam Brigades, which led the 7 October 7 attacks.

On 14 October 2023, an Israeli military spokesman called Sinwar “the face of evil”. He added: “That man and his whole team are in our sights. We will get to that man.”

Sinwar was also close to Iran. A partnership between a Shia country and a Sunni Arab organisation is not an obvious one, but both share a goal to end the state of Israel and “liberate” Jerusalem from Israeli occupation.

They have come to work hand in hand. Iran funds, trains and arms Hamas, helping it to build up its military capabilities and amass an arsenal of thousands of rockets, which it uses to target Israeli towns.

Sinwar expressed his gratitude for the support in a speech in 2021. “Had it not been for Iran, the resistance in Palestine would not have possessed its current capabilities.”

The loss of Yahya Sinwar will be a seismic blow to Hamas.

When the group chose him to replace Haniyeh as overall leader in August, it was a deliberate act of defiance and resilience. It could not have chosen a more uncompromising figure.

The group will now have to decide whether is the time to make a deal that ends the year-long Israeli military operation that has devastated the Gaza Strip.

Or, conversely, whether to continue fighting and resisting, hoping to outlast Israel’s patience, despite the horrendous death toll this conflict has wreaked upon Palestinian civilians.

US Secretary of State Antony Blinken said recently that a ceasefire deal in Gaza was “90% there”. The killing of Sinwar could be an opportunity to finally complete that deal and bring Israel’s hostages home.

It also risks doing the opposite: driving angry Hamas members further away than ever from any kind of compromise.(BBC)