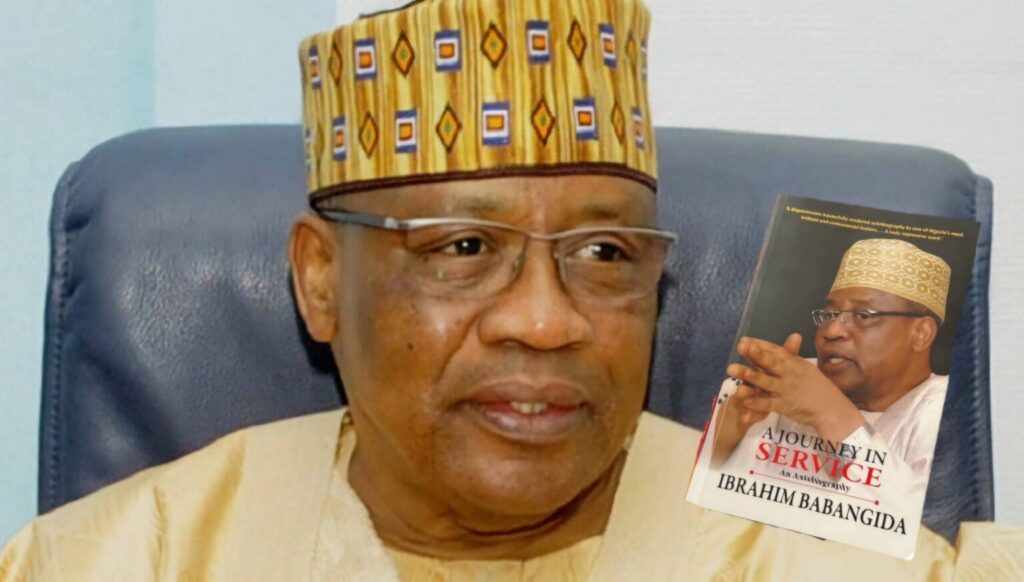

Former military president, General Ibrahim Babangida, retd, has said that former Head of State, Major General Muhammadu Buhari, retd, was overthrown in 1985 because he personalised leadership.

Sunday Vanguard recalls that Buhari was one of the leaders of the military coup of December 1983 that toppled ex-President Shehu Shagari.

But 40 years after Babangida seized power from Buhari through a palace coup, the former military administrator who ruled for eight years between 1985 and 1993, said Buhari and his deputy, the late Brigadier Tunde Idiagbon, displayed a “holier-than-thou” attitude, which led the country to a brink.

Babangida, who revealed this in his book: ‘A Journey in Service’, explained that Buhari opposed the civil populace and his constituency, the military.

Change in leadership was necessary

His words: “The change in leadership had become necessary as a response to the worsening mood of the nation and growing concern about our future as a people. All through the previous day, as we flew from Minna and drove through Lagos towards Bonny Camp, I was deeply reflecting on how we as a nation got to this point and how and why I found myself at this juncture of fate. By the beginning of 1985, the citizenry had become apprehensive about the future of our country.

The atmosphere was precarious and fraught with ominous signs of clear and present danger. It was clear to the more discerning leadership of the armed forces that our initial rescue mission of 1983 had largely miscarried.

We now stood the risk of having the armed forces split down the line because our rescue mission had largely derailed. If the armed forces imploded, the nation would go with it, and the end was just too frightening to contemplate. Divisions of opinion within the armed forces had come to replace the unanimity of purpose that informed the December 1983 change of government.

In state affairs, the armed forces, as the only remaining institution of national cohesion, were becoming torn into factions; something needed to be done lest we lose the nation itself. My greatest fear was that division of opinion and views within the armed forces could lead to factionalisation in the military. If allowed to continue and gain root, grave dangers lay ahead.

Antagonise the civil populace

“My predecessor in office, Major General Muhammadu Buhari, and his deputy, Brigadier Tunde Idiagbon, had separated themselves from the mainstream of the armed forces by personalising what was initially a collective leadership. They both posited a ‘holier than thou’ attitude, antagonising the civil populace against the military. Fundamental rights and freedoms were being routinely infringed upon and abused. As a military administration, we were now presiding over a society that was primarily frightened of us. We were supposed to improve their lives and imbue the people with hope for a better future.

Instead, we ruled the nation with a series of draconian decrees. An administration intended to reflect the collective will of the armed forces as a national institution came to be seen as the private personal autocracy of a stubborn few. Like most military coups, our leadership change was informed by widespread disquiet among the civil populace. Ordinary people were experiencing severe economic hardship. The general economic and social conditions the people lived under were worsening by the day.

Essential goods and supplies were scarce.

“Yet arbitrary controls in all aspects of economic life and an ancient resort to barter in international trade meant that the nation’s financial woes would not end soon. Draconian decrees led to the abuse and severe limitation of basic freedoms as people were clamped into indefinite detention, most times for minor infractions. Punishment for crimes against the state had led to the pursuit of mechanical legalistic justice against the dictates of natural justice. As the Chief of Army Staff, I was under undue pressure from the rank and file to seek ways of reconnecting the government to society lest we lose the nation itself.

Integrity of the Armed Forces

“On several occasions and instances, even the very integrity of the armed forces was being called into question. A disciplinary case involving allegations of divided interest against some senior officers was decided without due recourse to the Army Council. Instead of waiting for a report and investigation from the Army leadership, the affected officers were unceremoniously relieved of their commission, and their military career of so many years was abruptly ended without any input from the Army as their institution of origin. I objected to this arbitrariness and disregard for due process. I confided in some senior colleagues that I would rather resign my commission than continue in office as Chief of Army Staff without input into decisions that concern the careers of personnel under my command.

Surveillance

“In response, I was placed under surveillance, with the privacy of my communications and those of my family constantly monitored. This tense atmosphere culminated in the unanimous decision of a broad spectrum of senior and middle-level officers to change the nation’s leadership. The processes associated with this change were completed without bloodshed by midnight on August 26, 1985. ON AUGUST 27, 1985, I assumed office as the nation’s new leader, fully aware of the many challenge confronting the country. I had no illusions about the direction in which to move the country. I had long-standing convictions about Nigeria born of many decades of comprehensive consultations with a broad spectrum of compatriots from nearly all walks of life. Having been part of all previous government changes, I had become quite familiar with the wishes and aspirations of our people and developed a template of what needed to be done, at least from my modest perspective. The new administration’s determination was informed by a genuine desire to end the cycle of instability in both the politics and general history of the nation. I made this clear in my inaugural address to the nation.”

The former military leader also expressed regret leaving behind the late General Abacha, as the most senior military officer to work with the Interim National Government led by Earnest Shonekan, describing his action as a ‘grave mistake’.

Babangida denied knowing or having anything whatsoever to do with ABN, led by Senator Nzeribe, whose activities contributed immensely to the annulment of the June 12 election won by MKO Abiola.

Babangida admitted in the book: “While mapping out our strategies for the way forward, our credibility deficit persisted, compounded by several seemingly unrelated events. In March 1992, a hitherto unknown group named Association for Better Nigeria (ABN) emerged, headed and funded, we later found out, by the wealthy Igbo maverick Arthur Nzeribe, calling for four more years for the administration.

“The emergence of the group personally took me by surprise. But we were, as a government, so immersed in our credibility crisis that no one believed that I, or a member of our government (at least, to my knowledge at that time), had a hand in the group’s activities, especially also, as Chief Arthur Nzeribe was personally known to me. It was difficult in the circumstances that we now found ourselves having to persuade an already sceptical Nigerian population that we were not behind the campaign for an extension to military rule.

“It was a bewildering experience, even more so because, as we later found out, ABN was not even a formally registered organisation then. As I will show later, figuring out the real forces behind this shadowy organisation took a long time.

“Our problem of what to make of ABN’s activities was compounded by behind-the-scene pressure from various groups, including the political class, for us to remain in office! Recall that the elected State Governors had assumed office in January 1992.

“Suddenly, in our search for a way forward, some of the State Governors who had been elected through a process that we were trying to fine-tune for the Presidential elections were telling us, like ABN, to postpone the Presidential elections. I was alarmed. Yet, the same governors (with the possible exception of one or two) went back to their party Conventions to say that I had a hidden agenda to extend my stay in power! At moments like that, being President of a beautiful country like Nigeria became frustrating. You wished you didn’t have to confront these challenges in those rare, lonely moments.

“But our challenges were far from diminishing. If anything, they multiplied. While still engulfed by the shadowy activities of ABN and troubled by the unsolicited ‘advice’ of some state governors to extend our stay in office, we were suddenly confronted in May 1992 by a wave of communal, industrial, labour and student unrest on a scale that was frighteningly disturbing. The communal conflict in Zangon-Kataf in Kaduna State quickly spread like wildfire to other parts of the state. In Lagos and other parts of the country, violent protests over the effects of the Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP) had claimed lives.

Confession

Babangida alos recalled all the attempts made by Abacha and other unnamed senior military officers to truncate the transition programme in Nigeria at the time and confessed that he made a big gaff by allowing the former head of state to remain in power after he left office in 1993.

Babangida noted: “Without question, one of my biggest headaches at this time was Sani Abacha. I knew that Abacha was ambivalent about a return to civil rule. But I thought, in retrospect now, naively, that he would support our transition to civil rule programme.

“As I said earlier, Abacha and I had come a long way. We were good friends, and he had indeed been nice to me. As I have said elsewhere, he saved my life once and also risked his life to ensure that I took over in 1985. I could never forget those details.

“I obviously didn’t know everything about him! For instance, I was alarmed to discover that he and a handful of others mobilised negative opinions against me within the military, portraying me as the problem. That campaign was geared towards a violent military coup to remove me as President forcefully.

“Without question, the idea of an ING was a contraption, something of a compromise between the fierce Abacha-led opposition to the June 12 election results and the position that the election results be allowed to stay, one that will succeed our government after the August 27, 1993, exit date.

“To legally actualise that decision, the government directed Professor Ben Nwabueze and Clement Akpamgbo to draft an enabling law, Decree 61 of 1993, the legal framework for the ING. Although the political parties had suggested a few other names for headship of the ING, we, as a government, were okay with letting the Transition Council Chairman, Chief Ernest Shonekan, head the ING.

“Desirous of not being a stumbling block of any type, and as a personal sacrifice, on August 17, 1993, I announced my desire to ‘step aside’ and go into retirement during my address to a joint sitting of the National Assembly.

“The outgoing government also felt that it would be proper for the Service Chiefs to retire, namely Lt-General Ibrahim, Air Vice-Marshal Akin Dada, Vice-Admiral Dan Preston Omatsola, and Aliyu Attah. One didn’t need to be a soothsayer or an astute political scientist to see that Chief Shonekan would have a tough time on the job.

Although a former Chief Executive of UAC/Unilever, I feared he might lack the political astuteness to handle the impending national challenges. The situation was further complicated because, like Abiola, Shonekan was an Egba-Yoruba, which meant the new Interim government would be unpopular in Abiola’s strongest hold, southwestern Nigeria.

“Partly for the reasons stated above, we decided to provide adequate support to the new government by retaining critical top military officers from the outgoing Transitional Council I had headed, essentially as ‘enforcers’ for the new interim government.

“Accordingly, Lt-Generals Joshua Dogonyaro (as Chief of Defence Staff), Aliyu Muhammed Gusau (as Chief of Army Staff), and Brigadier John Shagaya (as GOC First Division) were retained.

“Problematic as it seemed, General Abacha also retained his position as the Chairman of the Joint Chief of Staff and, presumably, as enforcer-in-chief for the new government! But as we all now know, that was a grave mistake,” Babangida admitted.

Babangida also reflected on the controversial cancellation of the governorship primaries of the two political parties in 1991, saying that it was marred by allegations of rigging and other electoral malpractices.

He gave justification for the cancellation, saying, “The rescheduled primaries were successfully held in five states on December 3, 1991, but only after we had arrested and detained some 13 political ‘godfathers’ within the two parties, among them Maj-General Shehu Musa Yar’Adua, Alhajis Abubakar Rimi, Maitama Yusuf, Lateef Jakande, Lamidi Adedibu, Chiefs Bola Ige, Jim Nwobodo, C. C. Onoh. Arthur Nzeribe, Olusola Saraki and Solomon Lar”.

(Vanguard)