The recent executive order by President Donald Trump halting foreign aid for 90 days, and the likelihood of a longer pause in the foreign assistance, may cost Nigeria an average of $1 billion in health and other humanitarian interventions yearly if sustained.

Though the two countries are 11,472 km apart, the United States’ foreign assistance policy has traditionally raked in significant aid to Nigeria, with the highest sum of $1.16 billion spent in 2022, and $767 million in 2024.

Recall that the U.S. government announced a freeze on almost all new funding for foreign assistance programmes, with exceptions for allies Israel and Egypt. The order from the U.S. State Department at the weekend also includes exceptions for emergency food programmes, but not health programmes that supporters say provide vital, life-saving services.

Humanitarian organisations have expressed shock at the directive, voicing fears that it could contribute to global instability and loss of lives.

Should the aids stop, Nigeria would need to explore alternative sources to block holes created by the donor fund, which may include borrowing thereby compounding the country’s debt burden.

Presently, millions of Nigerians that are battling one ailment or the other, and rely heavily on U.S. assistance face an uncertain future. This freeze has the potential to disrupt vital health programmes, and economic growth, as well as, compromise security efforts that are pivotal to Nigeria’s development.

Nigeria has always been among the top eight priority countries of U.S. foreign assistance. A 2024 partly reported foreign assistance record obtained by The Guardian showed that Nigeria received $370 million in health funding; $310 million in humanitarian aid; $35 million went into administrative cost; $24 million on education; agriculture got $7.8 million and $7.4 was spent on other concerns last year.

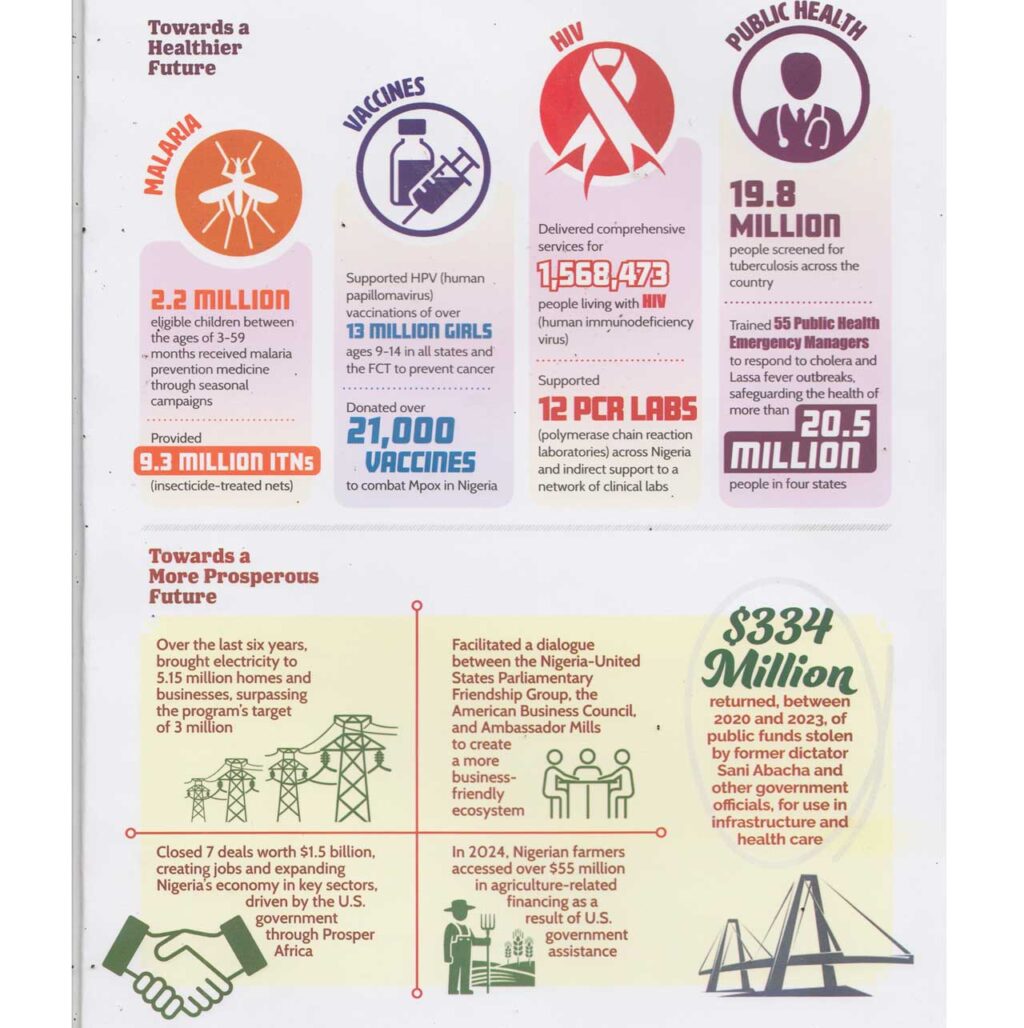

Specifically, the U.S. Diplomatic Missions in Nigeria, in its 2024 report, provided some details about assistance to different sectors of Nigeria’s economy.

It disclosed that the United States provided malaria prevention medicine to 2.2 million children aged three to 59 months as part of several campaigns.

Additionally, the U.S. supported 13 million girls aged nine to 14 with Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccinations aimed at preventing cancer.

Similarly, the U.S. made significant strides in the fight against HIV and tuberculosis, delivering services to 1.57 million people living with HIV; screening 19.8 million Nigerians for tuberculosis, and training 55 public health emergency managers to respond to cholera and Lassa fever outbreaks.

Within the economic sector, the U.S. closed seven deals worth $1.5 billion through Prosper Africa, creating jobs and expanding Nigeria’s economy. This is just as American aid helped students to access $30 million in scholarships, while more than 3.6 million teaching and learning materials were delivered to classrooms nationwide.

On the security front, the U.S. provided $40 million in military security assistance to Nigeria in 2024 and trained 60 members of the Nigerian military at professional military schools in America. The United States, in partnership with the Institute for Peace and Conflict Resolution, also deployed early warning software to quickly identify and address emerging conflicts in the region.

Furthermore, over $50 million was allocated for criminal justice and civilian security reforms, expanding legal aid services to over 5,000 Nigerians in courts and correctional centres. The United States support also provided farmers with over $55 million in agriculture-related financing.

Also worthy of mention, is the fact that through PEPFAR’s commitment to the global fight against HIV/AIDS, more than 17 million lives across 54 countries have been saved.

In Nigeria, the U.S. government has contributed more than $6 billion over the years to the national HIV/AIDS response, helping to significantly bolster the country’s efforts to tackle the epidemic and make strides toward meeting the UNAIDS 95-95-95 targets for ending HIV as a public health threat, by 2030.

PEPFAR, through the U.S. Embassy and Consulate in Nigeria, has been essential in providing life-saving HIV treatment to over 1 million women and children. The programme has also played a crucial role in reducing new infections and ensuring that millions of Nigerians have access to the treatment they otherwise would not have received.

With over one million women and children currently depending on PEPFAR’s support, the cessation of this funding could result in them being left without critical treatment, putting at risk the significant progress that Nigeria has made in combating HIV.

The U.S. spent more than $60b in foreign assistance in 2023, more than any other country overall.

A reliable source at the Institute of Human Virology Nigeria (IHVN) told The Guardian that the Trump administration’s 90-day freeze on foreign aid could have serious consequences for Nigeria.

The source explained that PEPFAR had been gradually reducing its involvement in the country in recent years, with the expectation that Nigeria would take on more responsibility for its HIV/AIDS and malaria programs. However, the Nigerian government has struggled to fully assume responsibility for these vital programs, leading to a reduction in U.S. support, including fewer supplies and reduced funding.

“With the ongoing reduction in funding and resources, if the U.S. pulls its remaining support, we will be in serious trouble. The progress we’ve made so far could be jeopardised,” the source said.

The 90-day freeze on foreign aid, as detailed in a memo received by U.S. diplomats, will impact both new and existing funding, including ongoing HIV/AIDS programmes. This directive, issued under President Trump’s executive order on foreign aid, has left many U.S. diplomats and public health experts surprised, and concerned about the future of these critical programmes.

Experts are increasingly worried that as Nigeria continues to face challenges in fully taking over its HIV/AIDS response, any further reduction in U.S. support could severely undermine efforts to control the epidemic, putting millions of lives in jeopardy.

In sharing his perspectives on the potential effects of the U.S. executive order halting funding specifically for HIV/AIDS programmes in Nigeria, the Director of Research at the Nigerian Institute of Medical Research (NIMR), Prof. Oliver Ezechi, noted that the gradual reduction in funding has been an ongoing process over the past decade, with the U.S. providing clear indications that a change was coming.

Now that the freeze is in effect, Ezechi maintained that the situation has both negative and positive sides.

On the negative side, he anticipated an initial disruption in HIV services, including treatment, diagnosis, and prevention programmes.

He acknowledged that these disruptions could cause challenges in the short-term, even though things would eventually stabilise depending on how well Nigeria handles the transition and assumes responsibility for the programmes.

Conversely, Ezechi expressed the belief that the reduction in funding could force Nigeria to take greater ownership of its HIV/AIDS programmes. This shift in responsibility, he suggested, could lead to more local involvement, making the programmes more sustainable in the long run.

He further expressed confidence that Nigeria can rise to the challenge with a growing pharmaceutical sector, where local manufacturers could play a significant role in supporting the programme.

Ezechi emphasised that Nigeria has a history of responding effectively to emergencies, and with the right resources, the local pharmaceutical industry can step in to ensure the continuity of HIV/AIDS treatment and services.

“The critical factor will be ensuring that these manufacturers have the necessary resources to maintain the HIV/AIDS response without interruption,” he noted.

Research professor at the Nigerian Institute of International Affairs (NIIA), Prof. Femi Otubanjo, said it is important to make a distinction between countries that are reliant on aids and those that receive them as supplementary resources.

He emphasised that these days, many countries do not depend on the United States for sustenance, noting that from his last fact check, Nigeria received about $1.1 billion in humanitarian aid in Donald Trump’s last tenure, which is not significant in terms of our national needs.

According to him, giving aids to other countries is an instrument of friendship used to develop and consolidate relationships. So if by any chance the aid is removed, you are undermining your own influence.

“They are undermining their own influence and that is not good for American foreign policy, if you want to put it in a very crude form. The countries will miss a little bit of support, but since no country depends on aids, it won’t be disastrous or fatal to their budgeting process, but would adversely affect their relationship with the country that is withdrawing aid.

“Then it becomes that that country is not reliable. You cannot depend on it and it also affects your perception and friendship of that country,” he said.

Otubanjo stressed that Trump is a transactional president, who seeks to identify benefits to transactions or actions.

“He sees it almost as a balance of trade relationship, that whatever they give you, you will be able to get more back. Whereas giving aids is not like that. You are not expecting anything back beyond goodwill and friendship,” he added.

(The Guardian)